Journal

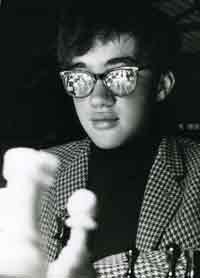

This is a picture of me in the days before I’d heard of Charles Babbage. It was taken in around March 1958: a time when computers had still to make any significant mark on the world and when IBM still made more money from tabulation machines that used punched cards than it did from its very large and cumbersome computers.

I was born in Leicester. As someone who’s interested in history, I can’t help setting my birth in some sort of historical context. I’d say that it was quite an interesting time to be born because the modern age of electronics, computers and global communications was being born at around the same time. My father wrote me a letter on the day I was born. This was remarkably prescient in many respects and contains the sentence:

The age of miracles is beckoning to you, to enter its phantastic realm. The age of power and light and machines that fly faster than the sunbeams lies at your feet, my son. The age of universal brotherhood is though a distant dream that may in your lifetime become a reality. God grant you the joy of living amongst all this and may you use the instruments, that we helped to forge, for the good of all mankind.

I was born into a family that was basically Anglo-German. My father Theodore Ted Essinger was born in 1922 into quite a well-to-do Jewish family in the German city of Chemnitz. His brother Uli was born in 1925. When you consider the terrible history of the Jewish community in Germany after 1930, it’s sobering to remember that many of the Jews who were living in Germany in the early decades of the twentieth century were descendents of Spanish Jews who had moved to civilised and humanist Germany a few hundred years earlier to escape oppression in Catholic Spain.

Neither my grandparents Julius and Rega, nor my uncle, Uli, survived the Second World War. Julius was interned while in German occupied France, where he had gone to try to find a safe haven where his family could join him. He was probably sent to a concentration camp during the war and presumably died there.

Neither my grandparents Julius and Rega, nor my uncle, Uli, survived the Second World War. Julius was interned while in German occupied France, where he had gone to try to find a safe haven where his family could join him. He was probably sent to a concentration camp during the war and presumably died there.

Rega, who was a nurse by profession, was alive as late as January 1944. She had been sent with the German army to the city of Reval (now Tallinn), the capital of Estonia with her son Uli. However, during the war they were separated and  Uli was sent to the town of Dorpat and Rega never saw him again. She herself remained with the German army in Reval until January 1944 when the Soviets invaded Estonia and forced the German army back.

Uli was sent to the town of Dorpat and Rega never saw him again. She herself remained with the German army in Reval until January 1944 when the Soviets invaded Estonia and forced the German army back.

There is a letter from Rega to one of her friends in Berlin written in January 1944 in which she speaks of terrible privations and the bitter cold. It seems likely that she perished while accompanying the German troops on the withdrawal from Reval. As a Jew, Rega was treated as a slave labourer and would have been last in the queue for food and medical assistance. In any event, nothing more has ever been heard of her and it is surely inconceivable that now anything ever will. Nazism killed my paternal grandparents and my uncle as it killed so many others.

One small, but significant, piece of retribution is that on October 16, 1946, the following former Nazis were hanged at Nuremberg for War Crimes.

Hans Frank

Walther Funk

Wilhelm Frick

Alfred Jodl

Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Wilhelm Keitel

Joachin Von Ribbentrop

Alfred Rosenberg

Artur Seyss-Inquart

Fritz Sauckel

Julius Streicher

Herman Goering committed suicide in his cell by swallowing cyanide shortly before he was due to be hanged. Martin Bormann was sentenced to death in absentia.

My father came to England in 1939, in July; only a couple of months before the War broke out. He was only seventeen at the time and I’ve always been conscious of this terrible trauma he suffered when, as a teenager, he was basically forced to leave his own country and go and live in a foreign country where he barely spoke the language to begin with.

The reason he was able to leave Germany – and of course if he hadn’t, I wouldn’t be here – was that he had an uncle – our Uncle Jules – who was his mother’s brother and who was a successful businessman in the garment trade. Jules had been head-hunted in the early 1930s by a Manchester clothing company and had come to England to run that company. Jules had to pay £100 to the German government in order to get my father out of Germany. It is also a sobering thought to think that it is this £100 that kept my father alive and, led to my brother and myself being born at all. In those days, £100 was probably around £3,000 today.

My father started working in Manchester. When war broke out he was interned for some time as were many German nationals who had recently come to Britain. He never saw his mother, father or little brother Uli again.

My father made a new life for himself in England and in 1952 met my mother at the Palais du Dance in Leicester. They were married in 1954 and still live in Leicester to this day.

I was born on September 5 1957. My brother Rupert was born on May 2 1961.

Rupert was found drowned in the Grand Union Canal, Leicester, on Tuesday January 22 2019, about four miles from where Mum (1931-2020) was living in a retirement community on the London Road, Leicester. Rupert, who lived in the United States, was temporarily staying with her. There is strong circumstantial evidence that he committed suicide although as there were no witnesses to him going into the water, it is at least possible his death was an accident. However I don’t think it was. Rupert had been very depressed about the failure of his marriage to his wife Christen. I tried very hard to help him but he didn’t want my help, nor my advice that it would be best if he had an amicable divorce from Christen and remain friends with her. He was a man of great intelligence and immense charisma. His death was a tragic waste of potential, but it did at least free him from the personal unhappiness that had plagued the last years of his life.

I was fortunate with my education. I went to a good local infant and junior school, Overdale. I can still remember the enormous enthusiasm the teachers had for what they did and I can still remember all the different activities in which we were involved. Funnily enough, I can actually remember the actual moment when I learned the meaning of one particular word: ‘omit’. I was probably about seven or eight at the time and on the blackboard in the morning it mentioned a hymn we would be singing in morning assembly, and that we had to ‘omit’ a particular verse. I didn’t know what this word meant and I remember asking a teacher to explain it.

I was very happy at school and was lucky, with hindsight, to go to a flourishing school that was attended by the sons and daughters of Leicester’s wealthy industrial and commercial community.

Leicester is not a particularly glamorous city and I never wanted to live there as an adult, but I do admire its vigour and when I visit Leicester nowadays I’m often struck by the breadth of the streets and rather splendid architecture. I think one can have a very good life there but I suppose I’m not the only person who wanted to spend his adult life living elsewhere from where he was brought up.

I was particularly interested in reading and in writing stories when I was younger and I’ve never lost interest in doing this. When I was eleven I went to a grammar school – Wyggeston Boys – where I was suddenly in a single-sex environment that I had been warned would be very demanding and very intensive but which always struck me as being fairly relaxed and pleasant. I loved learning Latin, French, Maths and of course English.

In my first year there I learned to play chess and became a keen player,  eventually reaching national standard when I was about sixteen, when I came third in one of the strongest junior tournaments ever held in London. But I was about to do my A-levels and discussed with my mother about the role chess should be playing in my life and decided to focus on my A-levels instead. I’m really glad I did make that choice because while I think chess is great fun – and I still play today for a local chess team – I’m suspicious of it as a full-time activity. I think it’s insufficiently creative, not productive in any particular sense, and I’m not convinced that the intellectual skill of playing chess is transferable to anything more useful.

eventually reaching national standard when I was about sixteen, when I came third in one of the strongest junior tournaments ever held in London. But I was about to do my A-levels and discussed with my mother about the role chess should be playing in my life and decided to focus on my A-levels instead. I’m really glad I did make that choice because while I think chess is great fun – and I still play today for a local chess team – I’m suspicious of it as a full-time activity. I think it’s insufficiently creative, not productive in any particular sense, and I’m not convinced that the intellectual skill of playing chess is transferable to anything more useful.

Not that I want to be rude about chess. I’ve several really good friends who I’ve met through the game while playing in occasional tournaments and for my local club, which meets at the Plough & Harrow every week in the village of Bridge near Canterbury. I find chess a brilliant recreation and a sort of ‘mental mouthwash’ which in moderation is a good deal of fun. I tend to think chess is the most fun when there isn’t too much at stake in the game and you can really try to think of some interesting ideas and make the pieces come alive.

One of my proudest moments in my early chess career was when Chess magazine accepted a short article I’d written about a particular chess opening, the Sicilian Defence. This was published in the November 1974 issue. I received £1 for it.

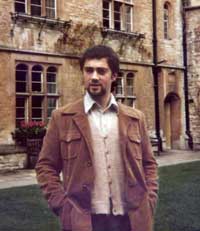

In 1978, when I was 21, I went to Lincoln College, Oxford, where I read English Language and Literature. I wrote my first novel at Oxford. Predictably enough it was about a sixth-former who went to University, although for artistic reasons I decided he would go to Cambridge rather than Oxford. I don’t suppose it was any good, but I’ve since discovered with writing that you have to write a lot of stuff that isn’t any good in order to teach yourself to write stuff that is better.

I made some good friends at Oxford but I can’t honestly say it was the happiest time of my life. I went to Oxford when it was still substantially a single-sex. Having been to a single-sex school I really needed some emotional education rather than just intellectual development. With hindsight I’d’ve probably have been happier at a more mixed university where they would’ve been a greater chance of finding a serious girlfriend. Although I did have a sort of semi-girlfriend at Oxford for a few months, it never went anywhere and I left Oxford untutored in the arts of love, so to speak.

All the same, I did have wonderful teaching at Oxford and read most of the masterpieces of English literature, so I shouldn’t complain. Also, in those days, students actually got government grants, so I didn’t leave Oxford with a mountain of debt.

One very exciting development in my life during my university days was that I spent two summer vacations working in Germany, in Dusseldorf. During the second vacation I met some Finnish people of my own age and became friends with them. I got really interested in the Finnish language, and in my third year at Oxford I made efforts to learn it, with some success. I advertised locally to find two Finnish people to practise Finnish conversation.

Because of my interest in Finnish I was very keen to go and work there after University. One way of doing this was to teach English as a foreign language (TEFL) through the British Council. Most of these appointments required the candidate to have completed a one-year course in TEFL. But because Finland was not a particularly popular destination (in fact, some teachers were prone to get despondent and come home after only a week in their postings) I didn’t need to complete a TEFL course before going to Finland.

I spent my first nine-month contract in a coastal town in Western Finland called Pori, which was reasonably good fun, but not a very inspiring place to live, or at least not for me. However, in my second and third postings out there I went to live in a wonderful town called Jyväskylä, where I was very happy from the beginning. I actually managed to find a girlfriend, or indeed three. I still have good friends in Jyväskylä and go back when I can afford it.

Some of my closest friends in Jyväskylä are the Trzaska family. The father, Wladek, is one of Finland’s leading nuclear physicists and was born in Poland. His wife, Tiina, is Finnish. They actually met at one of my fancy dress parties! They have two brilliant children, Sebastian and Elsa.

None of the writing I completed in Finland was of publication standard, but I’m quite proud of a short story I wrote at that time called ‘In the land of the Lapps’. This was inspired by a marvellous short story by the German writer Heinrich Böll entitled ‘Im lande des Rujuks’. Böll’s story is an account of an academic who can’t really deal with life and who devotes many years to mastering the language and culture of an alien people, and then journeys there and finds nothing but disillusionment. I thought it would be fun to adapt this to the Lapp culture, which even the Finns find rather romantic and remote. The Lapp language I have used is invented. I think this story works quite well, although that’s mainly because Böll provided the basic plot and structure. My own version of Böll’s story is hardly brilliant, but it’s not too bad and I don’t feel embarrassed in putting it on my website.

I came back to England from Finland in 1983. After six months teaching at a local academy in Leicester I started a career as a PR consultant in a small consultancy in London. I had written drafts of novels throughout my time in Finland and continued to practise this vice in London. I found and find PR a fascinating thing to do and after working in various consultancies in London I set up in business myself as a PR consultant in March 1989. Since then I have worked in PR and had about thirty business books published. In 1998, while still doing public relations, I very consciously decided to stop writing business books and to embark more concertedly on writing more general, mass-market books.

I currently live in Canterbury, where I moved in 1986. While I’m often in London on business, I really like living in Canterbury because the small size of the community suits my personality and I find it a very pretty town. I often think that living in modern Canterbury, and being able to walk to see one’s friends, is probably not unlike living in fashionable London in, say, the 1840s, when all one’s friends were likely to live quite close by. However, by the 1850s this kind of friendly fashionable London was starting to become noisy and rather too big.

Charles Babbage often refers to his increasing impatience at the noise and hubbub of London. I suspect that he, like me in a way, was essentially an eighteenth-century person at heart. Not that I would like to go and live in the eighteenth century, or even the nineteenth century for that matter. I rather share Woody Allen’s view that it would be no fun to live in any past time before antibiotics were invented.